My peers at Mozilla are running workshops on opportunity sizing. If you're unfamiliar, opportunity sizing is when you take some broad guesses at how impactful some new project might be before writing any code. This gives you a rough estimate of what the upside for this work might be.

The goal here is to discard projects that aren't worth the effort. We want to make sure the juice is worth the squeeze before we do any work.

If this sounds simple, it is. If it sounds less-than-scientific, it is! There's a lot of confusion around why we do opportunity sizing, so here's a blog post.

The Motivation

Last year we ran a huge A/B test over a full Firefox release (I mentioned this experiment before). Unfortunately, we didn't see the impact we were hoping for when we reviewed the results.

It was clear why we weren't seeing that impact once we did some back-of-the-napkin math. Our features just didn't affect a broad enough set of users.

I've fallen into this trap myself. I've developed a pretty good sense of how much effort a piece of technical work will take. However, I find I don't have a great intuition about how impactful a project will be.

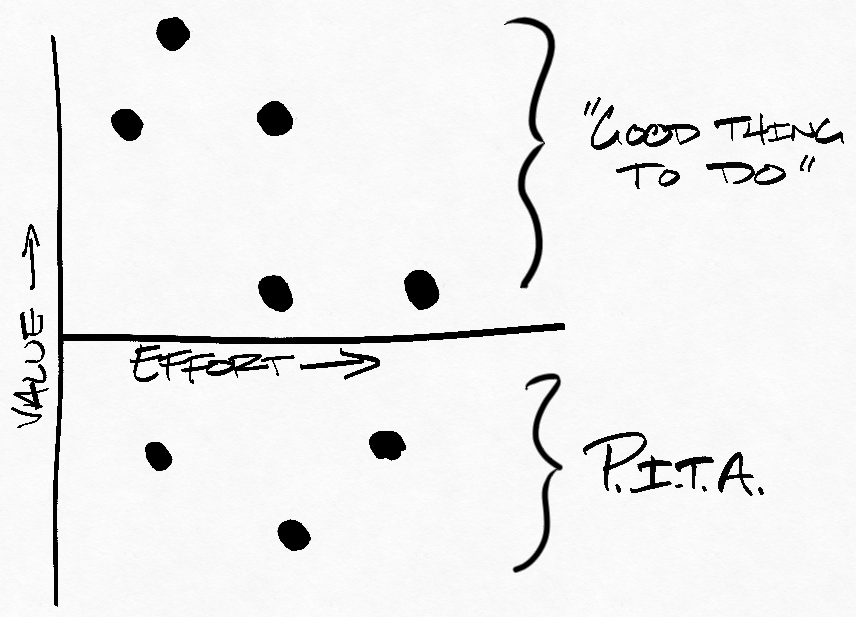

Instead, my brain seems to group all new projects into one of two categories: "Good thing to do" and "Pain in the a**" (PITA). A feature is generally a "good thing to do" if it would improve the product. On the other hand, it's a PITA if we're trying to contort the product into doing something it isn't meant to do.

Here's a doodle-graph to summarize. Each dot is a project:

On the surface this may seem fine, but it's a pretty bad heuristic in practice.

I'm not concerned about ignoring projects that look like a PITA. This isn't great, but usually someone will make some noise if I'm ignoring an important project.

On the other hand, projects in the "good thing to do" bucket are dangerous. Sure, this bucket has some good projects, but there are usually even more projects that aren't worth the effort. These are the projects that are "nice-to-haves" and hard to say "no" to. If you work on one of these projects, nobody's going to tell you you're wasting your time.

When choosing our work, we need to set the bar higher than "good thing to do". A feature needs to be designed, built, and released. If we're not careful, these costs can far outweigh any possible upside. There's also the opportunity cost— all the time we spend working on a "good thing to do" keeps us from working on more important projects.

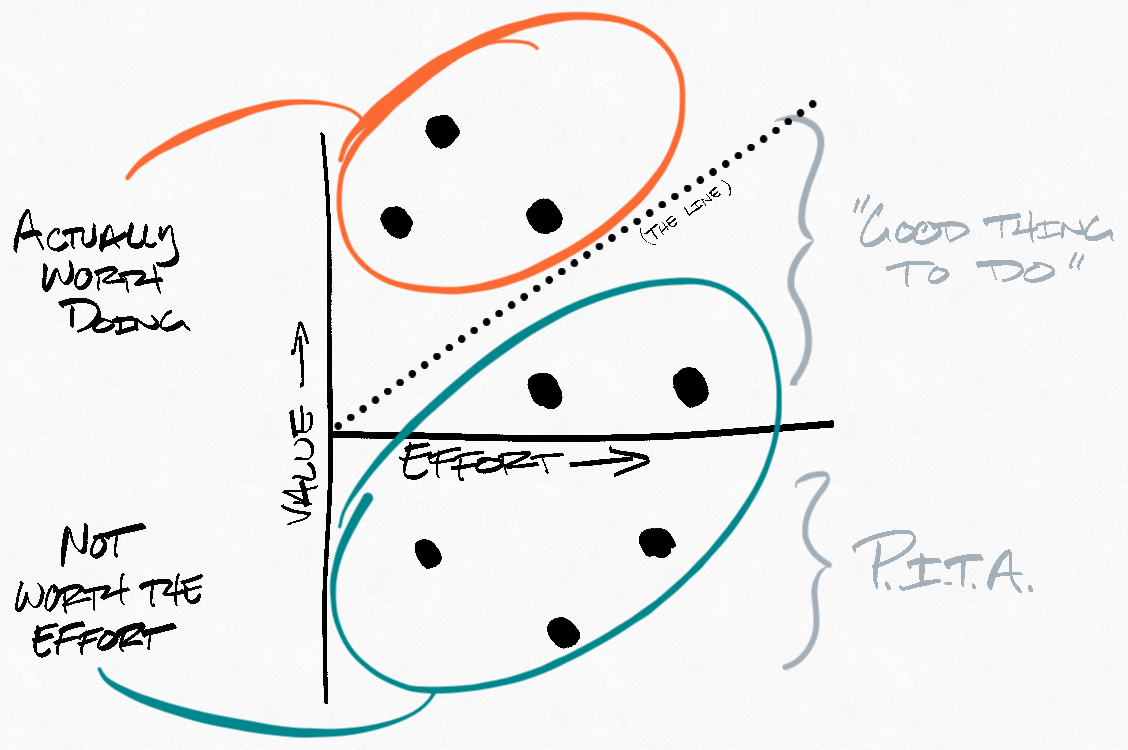

Instead of just looking at whether a project has some value, we need to make sure the value is greater than the cost. On our graph that would look like this:

Only some of the "good things to do" are actually worth doing. The rest have some value, but would take too much effort to make it worth while.

This also means we can't just work on whatever project has the most upside. Sometimes, all of the available projects are below the line (not worth the squeeze). In that case, it can be better to focus on finding more opportunities.

In short, picking arbitrary projects that are "good things to do" is a great way to waste a lot of time.

A Framework for Mozilla

Opportunity sizing helps us break free from this default heuristic and think about our projects with more structure. The framework seems too simple to yield any real insight, but I'm consistently surprised at how helpful it can be.

In this way, opportunity sizing is like a checklist in its unreasonable effectiveness.

The framework we use at Mozilla needs three basic ingredients to size an opportunity:

- How many users could this project affect?

- What percent of users are going to change?

- How will those users change?

We usually have pretty solid data for #1 (How many users could this affect?). For numbers 2 and 3 we're looking for guesses that do a good job of communicating our assumptions. These guesses are informed by data, but are usually less-than-scientific.

Multiplying 1x2x3 gets us to a place where we can have a conversation.

But isn't that subjective?

Yup. But subjective analyses can still be useful.

To start, guessing at the opportunity size helps clarify our assumptions and identify weak assumptions early-on. Even better, this framework is a useful communication tool. "We don't have data, but this feels right" is good enough at this stage.

It does have to feel right though. Hopefully you're sharing these results with your peers. They can gut-check your work and you can together build a shared opinion. If your numbers are outrageous, you'll need to be able to defend them.

There's often concern that ambitious coworkers are going to oversell their opportunity to prioritize their pet-project. In my experience, there's not much incentive to do this. Eventually we either recognize over-hyped numbers and redirect the project or get underwhelming results from the launch and learn our lesson the hard way.

But what if you're wrong?

I am wrong. It doesn't matter.

First, this analysis should not be the entirety of our decision making process. It's a tool to break through some common biases when choosing work.

Second, these analyses can (and should) grow with our commitment to the project.

When we're early in the product life-cycle, we can make very rough estimates. As the project matures and we learn more, these analyses should mature as well. When we're deciding whether to commit 20 engineers for 6 months, we should have more confidence in our estimates.

We'll get better at this as we build more intuition. Our tenth opportunity sizing will be better than our first.